What is a Retinoblastoma?

Retinoblastoma is the most common eye cancer in children globally. Affecting 1 in every 12,000 to 15,000 children, it typically manifests around 2 years of age. However, instances have been noted as early.

Retinoblastoma is a tumour that originates in the retina, which is the inner lining in the back of the eye responsible for vision. Retinoblastomas are the most common primary paediatric ocular neoplasm in children.

Left untreated, the disease often progresses beyond the eye, infiltrating the eye socket, the brain, and eventually other parts of the body, leading to fatalities. Thus, it is not only sight-threatening but also life-threatening.

Who Manages Retinoblastoma at NUH?

At NUH, Retinoblastoma is primarily managed by a team of experienced specialists including paediatric ophthalmologists, retinal specialists, and eye plastic surgeons. This collaborative effort forms the core of our ocular oncology team. The multidisciplinary approach extends to include geneticists, ocularists (specialists in artificial eyes), interventional radiologists, radiation oncologists, and pathologists.

With over two decades of experience, we annually manage 8-10 new Retinoblastoma cases, providing extensive, long-term follow-up care for both seeing and surviving children. The disease is thoroughly staged through appropriate investigations, and individualised treatment plans are crafted. Long-term monitoring involves the joint efforts of ophthalmologists and oncologists, with additional genetic counselling provided by Geneticists.

Is Retinoblastoma Deadly?

Early diagnosis and intervention contribute to a remarkable survival rate of over 90-95%. Children who receive timely treatment lead normal lives, attending school and engaging in regular activities. However, when left untreated or poorly treated, almost all confirmed retinoblastoma cases spread beyond the eye(s) into the eye socket or the brain, and eventually to other parts of the body resulting in death.

What Are the Signs / Symptoms of a Retinoblastoma?

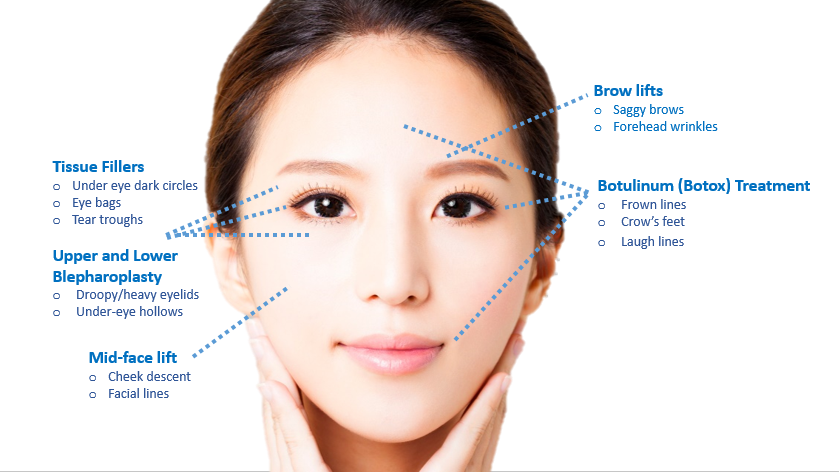

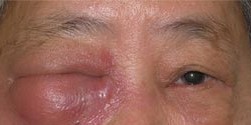

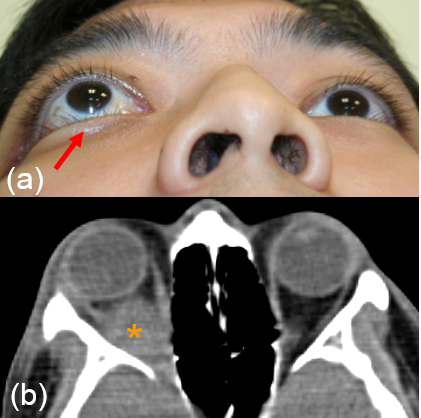

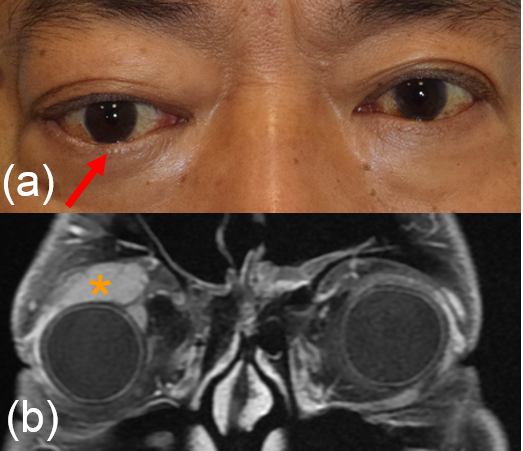

It is most commonly presented as an altered light reflex in the affected eye (white reflex, or leucocoria) typically seen in flash photographs of a child in the first 1-2 years of life (Fig. 1). Other manifestations include a new onset of 'cross eye' ('squint', strabismus), a non-responsive red eye to treatment, vision impairment, or late-stage manifestations such as eye enlargement or bulging. Advanced cases may present with systemic symptoms like irritability, failure to thrive, seizures, or swelling in other body parts due to metastasis. Parents who notice any of the early signs should promptly consult an eye specialist or paediatrician.

How Is Retinoblastoma Diagnosed?

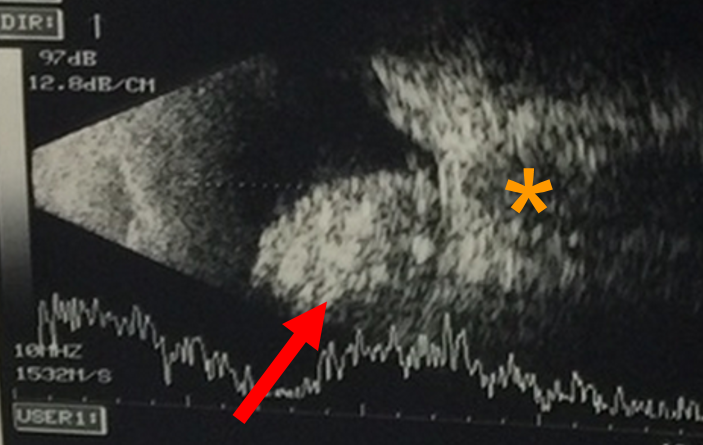

When signs indicative of Retinoblastoma are observed, the initial evaluation involves a thorough examination by an eye specialist. This examination is often followed by a more detailed assessment under anaesthesia or sedation. Diagnosis primarily relies on clinical examination, assessing the tumour's appearance and characteristics. Additionally, ultrasound scan is commonly used to identify calcifications and measure the tumour's size and potential spread beyond the eye. The use of a specialised fundus camera (RetcamR) aids in documentation, family education, communication with specialists and seeking second opinions when necessary.

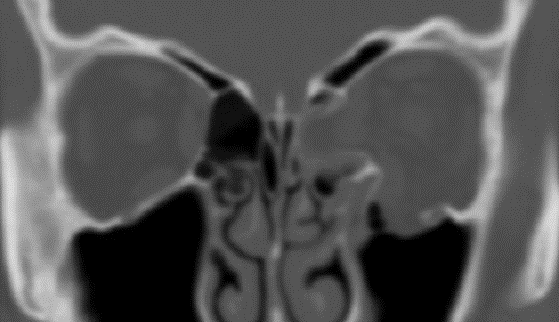

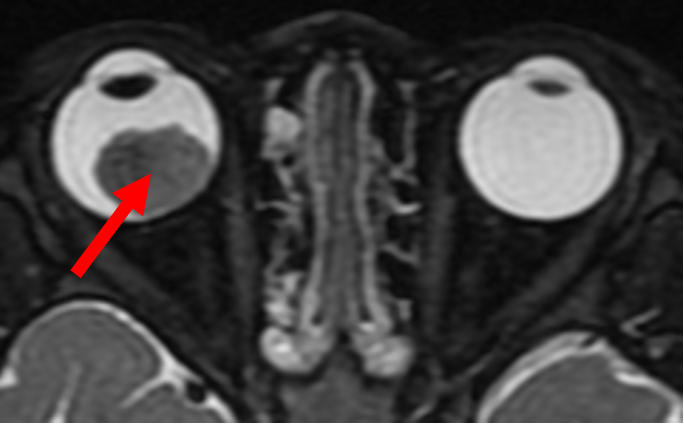

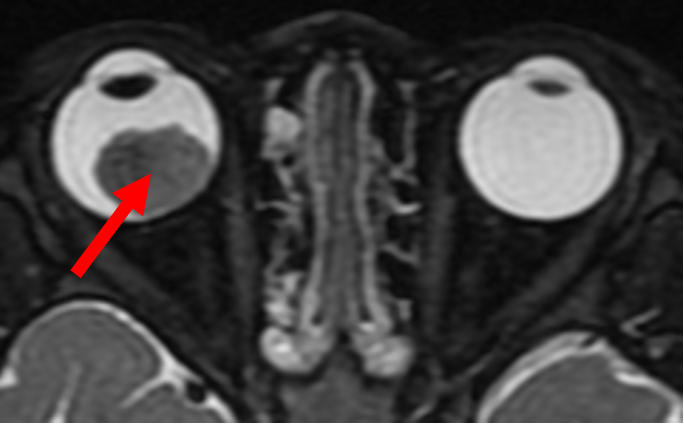

In cases where the disease is suspected to extend beyond the eye or affects both eyes, imaging of the orbit (eye socket) and brain is conducted to rule out extraneous spread and assess the presence of a rare third tumour in the brain (pinealoblastoma).

For patients presenting late with evident spread outside the eye, procedures such as lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis and bone marrow examination may be performed to confirm disease spread.

Note: This is one of the very few cancers where diagnosis is made and treatment is started without first performing a biopsy.

Newer Forms of Treatments Options

Recent years have witnessed the introduction of various advanced treatment options for Retinoblastoma, with some available at NUH. These include plaque brachytherapy (local radiation), intra-arterial chemotherapy (administered through blood vessels accessed via thigh blood vessels), intra-vitreal chemotherapy (direct injections into the eye, but it is not yet considered a primary treatment), and Autologous Stem Cell Rescue (ASCR)/Bone Marrow Transplantation (BMT) for late-stage metastatic disease.

How Is Retinoblastoma Treated?

The primary goal in the treatment of retinoblastoma entails the preservation of life, followed by the eye and subsequently, vision. Close teamwork within a multidisciplinary team comprising ophthalmologists, paediatric oncologists, geneticists, interventional radiologists and pathologists is essential to achieving those objectives. At present, retinoblastoma is one of the most curable paediatric cancers.

Staging the disease

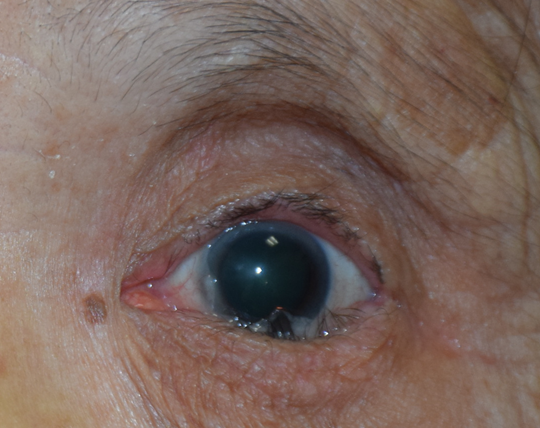

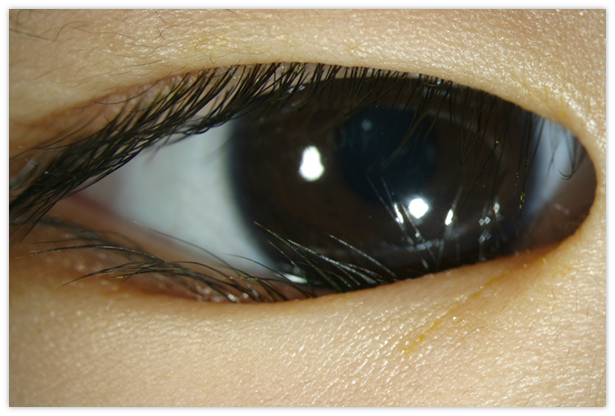

To determine the most suitable treatment, a thorough evaluation to stage the disease has to be performed. In young children, who may not cooperate with awake eye examination, assessment is usually done under sedation or anaesthesia. The pupils are dilated so the entire retina can be examined to determine whether there is one or more retinoblastomas. The examining doctor will also assess for seeding into the vitreous or front chamber of the eye.

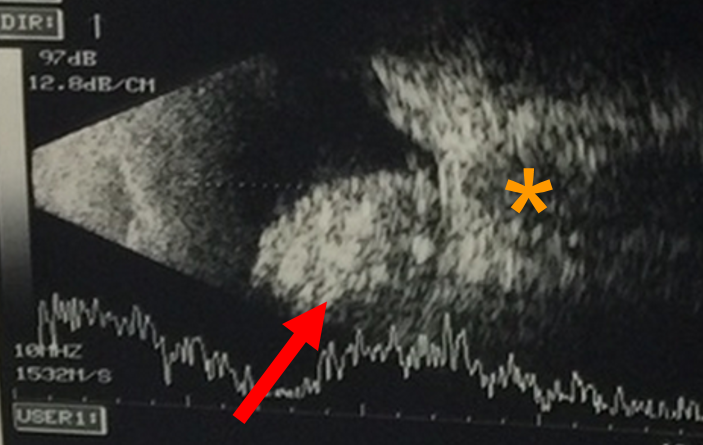

An ultrasound of the eye (Fig. 1) is performed to evaluate for characteristic features for the tumour like calcification, and to measure the size of the tumour. agnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbit (Fig. 2) is conducted to explore potential tumor spread outside the eye or into the brain. Importantly, both ultrasound and MRI procedures involve no exposure to radiation, ensuring a safe diagnostic process.

Treatment options

Various treatment modalities are available in the management of a retinoblastoma.

- Photocoagulation or cryotherapy can be used for the treatment of small tumours.

- For medium to large tumours with no systemic spread, enucleation is an established treatment. While this ensures the elimination of the tumor, it results in the complete loss of visual potential in the affected eye. Enucleation remains the treatment of choice for advanced unilateral disease with no prospect of functional vision.

- In situations where the disease is less severe, and there is potential for vision in the affected eye, several globe salvage treatments are available. These include:

Intra-arterial chemotherapy. NUH offers state-of-the-art Selective Intraarterial Chemotherapy for Retinoblastoma, performed by a neurointerventional radiologist. This is complemented by intraocular laser therapy, cryotherapy, and intravitreal chemotherapy administered by our Ophthalmologists. Additionally, systemic chemoreduction provided by our pediatric oncologists ensures a comprehensive, multimodal, and multidisciplinary approach to managing Retinoblastoma.

This treatment involves the super-selective infusion of chemotherapy into the ophthalmic artery—the blood vessel that delivers blood to the eye. This maximises the bioavailability of the drug in the targeted ocular structure, while minimising systemic drug exposure.

The current chemotherapeutic regimen used in intraocular chemotherapy comprises single or combined use of these three agents: melphalan (most commonly), topotecan or carboplatin. Introduced in 2006, this treatment has proven effective, especially in cases classified as advanced group D or E disease. A review comparing this method to primary enucleation showed no increased risk of orbital recurrence, metastatic disease or death.

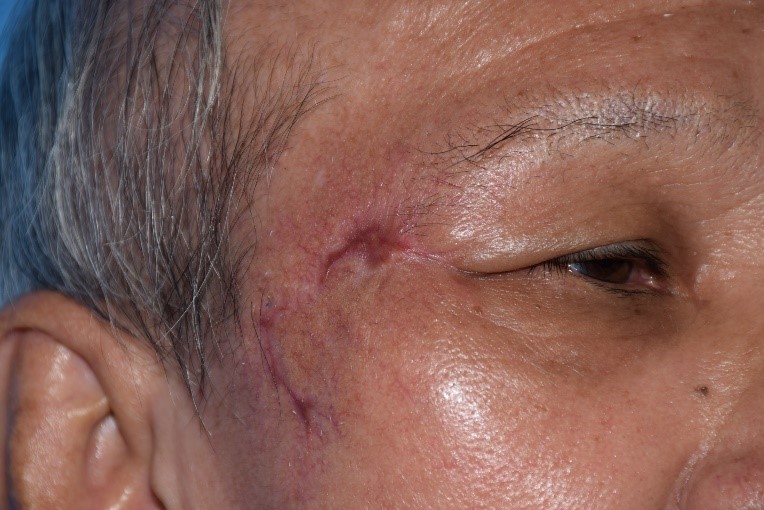

While generally safe, there are potential side effects associated with intra-arterial chemotherapy. Transient effects, typically resolving within six months, may include eyelid swelling, eyelid drooping, loss of lashes, skin redness over the forehead, and temporary limitations in eye movements. More serious potential side effects involve occlusion of the retinal artery or vein and choroidal atrophy, which may result in visual loss. Systemic side effects also include low white blood cell counts, risk of stroke and allergic reactions.

- Intra-vitreal chemotherapy involves the injection of medication directly into the vitreous cavity of the eye to treat refractory and recurrent seeding of the tumour into the vitreous. Reported complications include cataract formation, bleeding in the vitreous cavity, retinal haemorrhage and low eye pressures. There is also a risk of introducing infection into the eye, potentially leading to a loss of vision. Additionally, it carries a theoretical risk of tumour cells spreading through the needle track. Techniques used to minimize this risk include applying cryotherapy to the injection site before removing the needle, or using distilled water to wash the eye after needle removal. Distilled water has been shown to be effective in killing retinoblastoma cells in culture within a few minutes.

- Systemic chemotherapy is another option to achieve globe salvage, often preserving useful vision. However, it comes with potential risks, including an increased likelihood of secondary tumours such as leukaemia, low blood counts, kidney toxicity, and hearing loss. However, in cases with metastatic disease, multiple-agent intensive systemic chemotherapy is utilized to target tumour cells that have disseminated to other parts of the body.

- Radiotherapy has generally fallen out of favour because of the subsequent risk of second cancers, prompting a shift towards more efficacious and safer treatment options

Surveillance

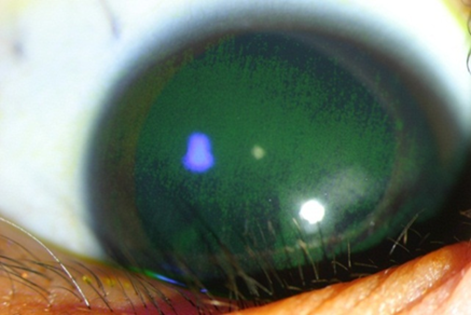

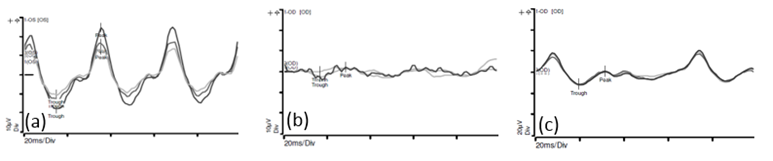

The electroretinogram (ERG) is an objective and non-invasive method for evaluating the visual pathway (Fig. 3). This diagnostic technique involves recording electrical signals produced by the retina in response to a brief flash of light. A reduction in ERG amplitude has been correlated with the degree of retinal disruption or toxicity. At our centre, ERGs are routinely conducted before each intra-arterial chemotherapy session to monitor retinal function.

Following successful treatment with regression of the tumour, surveillance has to be continued due to the potential for recurrence of disease or development of additional eye tumours.

Fig. 3 (a) This is the recording of the electrical activity in a normal eye

(b) This is the recording of the electrical activity in an eye affected by a retinoblastoma. There is reduced amplitudes and loss of the normal sinusoidal pattern.

(c)This is the recording of the electrical activity of the eye shown in (b), after 2 cycles of intra-arterial chemotherapy. There is improvement in the amplitudes and more semblance to the normal sinusoidal pattern.

Will the Eyes Be Taken Out?

Overall, the need for removal of the eye to treat Retinoblastoma has diminished substantially. Once a primary intervention, eye removal is now considered only after exhausting all other eye-preserving option, such as systemic or intraarterial chemotherapy. It is predominantly recommended for older children (above 2 years) with advanced cancer in a single eye, providing a fast and effective therapeutic approach while minimising potential complications associated with alternative treatments.

Note: An eye is usually removed only when absolutely necessary and is no longer the primary treatment option.

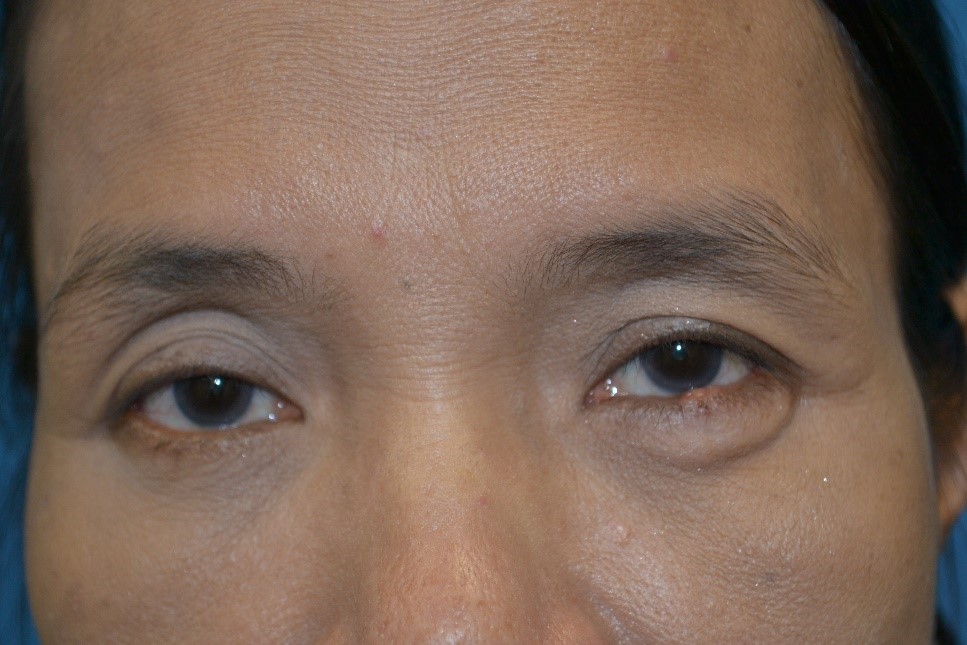

Will My Child Appear Normal After Removal of the Eye?

Despite undergoing eye removal, most children can be successfully rehabilitated to appear and function normally. After the eye is removed and any residual tumour in the eye socket is cleared, an "orbital implant" is inserted during the initial surgery. This implant is connected to the child's eye muscles to ensure adequate volume and reasonable movement. While the child recovers from the surgery, a temporary 'artificial eye', a customized iris painted conformer, is placed until a definitive customised 'artificial eye' (prosthesis) is fitted after 6-8 weeks, when most of the swelling from the surgery has subsided.

Can My Child Go to School Once Treated?

All children who have been treated are advised to wear protective spectacles with polycarbonate lenses, preferably tinted. These spectacles serve a dual purpose by not only shielding the eye(s) but also concealing subtle differences in appearance between the eyes. This precautionary measure ensures that children can engage in their daily activities, including physical exercises and studies, with a sense of normalcy. For children wearing a prosthesis (artificial eye), it is advised to wear protective goggles during swimming and contact sport. However, extra caution should be taken to prevent any injury to the normal eye.

Once Treated, How Long Should My Child Be Followed Up?

Once treated and completely rehabilitated, most children require regular and close follow-up until the age 5 years, and subsequently every 6-12 months until the age of 10. Thereafter, annual follow-ups with their eye specialists and paediatricians may be needed throughout their lifetime.

Is This A Genetic Disease? Why Should We Consider Genetic Testing?

Retinoblastoma is the first cancer with an identifiable genetic mutation. Approximately 15-20% of children with retinoblastoma in one eye and all children with the condition in both eyes are likely to possess an identifiable genetic mutation. Once identified, this mutation can be used to screen siblings and parents for similar mutation. Such insights not only guide parental counselling but also identify other children susceptible to the disease. Furthermore, this approach diminishes the risk of transmitting the mutation to subsequent generations when these children reach adulthood. For children without the mutation, this approach minimizes the need for aggressive, repeated examinations under anesthesia, easing parental concerns.

How Is Genetic Testing Done?

Most children are referred to the paediatric geneticist and counselled based on the family history and presentation. With informed consent, blood samples are collected and sent to national or international referral centres for genetic mutation analysis. In specific cases where the eye is removed prior to chemotherapy, tumour samples may also be used to identify genetic mutations.

Where Do NUH’s Retinoblastoma Patients Come From?

Apart from treating Retinoblastoma patients in Singapore (averaging 2-3 per year), our patients come from Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Russia.